Mexican American War

The Mexican–American War, also known as the Mexican War, the U.S.–Mexican War or the Invasion of Mexico, was an armed conflict between the United States ..

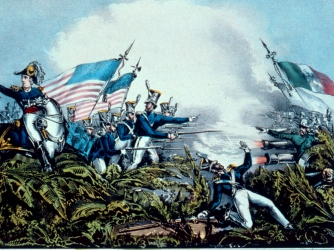

An illustration depicting a battle in the Mexican-American War. Library of.. He sent an American diplomat, John Slidell, to Mexico City to offer $30 million for it.

Find out more about the history of Mexican-American War, including videos, interesting articles, pictures, historical features and more. Get all the facts on ..

Mexican-American War, also called Mexican War, Spanish Guerra de 1847 or Guerra de Estados Unidos a Mexico (“War of the United States Against Mexico”), ..

The Mexican–American War, also known as the Mexican War, the U.S.–Mexican War or the Invasion of Mexico, was an armed conflict between the United States and the Centralist Republic of Mexico (which became the Second Federal Republic of Mexico during the war) from 1846 to 1848. It followed in the wake of the 1845 U.S. annexation of Texas, which Mexico considered part of its territory, despite the 1836 Texas Revolution.

When war broke out against Mexico in May 1846, the United States Army numbered a mere 8,000, but soon 60,000 volunteers joined their ranks. The American ..

Mexican–American War

Between 1846 and 1848, the United States and Mexico, went to war. It was a defining event for both nations, transforming a continent and forging a new identity ..

Nov 11, 2014.. The Mexican-American War was the first major conflict driven by the idea of "Manifest Destiny"; the belief that America had a God-given right, ..

Causes of the Mexican-American War The Mexican-American War Begins Mexican-American War: U.S. Army Advances Into Mexico Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo Ends the Mexican-American War The Mexican-American War (1846-1848) marked the first U.S. armed conflict chiefly fought on foreign soil. It pitted a politically divided and militarily unprepared Mexico against the expansionist-minded administration of U.S. President James K. Polk, who believed the United States had a “manifest destiny” to spread across the continent to the Pacific Ocean. A border skirmish along the Rio Grande started off the fighting and was followed by a series of U.S. victories. When the dust cleared, Mexico had lost about one-third of its territory, including nearly all of present-day California, Utah, Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico. On April 25, 1846, Mexican cavalry attacked a group of U.S. soldiers in the disputed zone under the command of General Zachary Taylor, killing about a dozen. They then laid siege to an American fort along the Rio Grande. Taylor called in reinforcements, and–with the help of superior rifles and artillery–was able to defeat the Mexicans at the battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma. Following those battles, Polk told the U.S. Congress that the “cup of forbearance has been exhausted, even before Mexico passed the boundary of the United States, invaded our territory, and shed American blood upon American soil.” Two days later, on May 13, Congress declared war, despite opposition from some northern lawmakers. No official declaration of war ever came from Mexico. At that time, only about 75,000 Mexican citizens lived north of the Rio Grande. As a result, U.S. forces led by Col. Stephen W. Kearny and Commodore Robert F. Stockton were able to conquer those lands with minimal resistance. Taylor likewise had little trouble advancing, and he captured Monterrey in September. With the losses adding up, Mexico turned to old standby General Antonio López de Santa Anna, the charismatic strongman who had been living in exile in Cuba. Santa Anna convinced Polk that, if allowed to return to Mexico, he would end the war on terms favorable to the United States. But when he arrived, he immediately double-crossed Polk by taking control of the Mexican army and leading it into battle. At the Battle of Buena Vista in February 1847, Santa Anna suffered heavy casualties and was forced to withdraw. Despite the loss, he assumed the Mexican presidency the following month. Meanwhile, U.S. troops led by Gen. Winfield Scott landed in Veracruz and took over the city. They then began marching toward Mexico City, essentially following the same route that Hernán Cortés followed when he invaded the Aztec empire. The Mexicans resisted at Cerro Gordo and elsewhere, but were bested each time. In September 1847, Scott successfully laid siege to Mexico City’s Chapultepec Castle. During that clash, a group of military school cadets–the so-called niños héroes–purportedly committed suicide rather than surrender. Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo Ends the Mexican-American War Guerilla attacks against U.S. supply lines continued, but for all intents and purposes the war had ended. Santa Anna resigned, and the United States waited for a new government capable of negotiations to form. Finally, on Feb. 2, 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, establishing the Rio Grande and not the Nueces River as the U.S.-Mexican border. Under the treaty, Mexico also recognized the U.S. annexation of Texas, and agreed to sell California and the rest of its territory north of the Rio Grande for $15 million plus the assumption of certain damages claims.